NAAR: Shayfeen is a Moroccan rap band and Moroccan society is rather suspicious of rap music. Did it slow down your career?

Shobee: It did in the beginning. There was a misunderstanding of what we did, of what was happening but now I don’t think society slows down or fears rap. Now it’s what people want, it’s the music that is listened to the most. We never felt a rejection of the public, a rejection of what we did. We just had to fight more for people to understand us. It’s that misunderstanding that slowed us down, that slowed down most artists who wanted to make rap in Morocco. But it’s more the lack of an industry that can slow down artists here. In the beginning, we didn’t have the freedom to say what we wanted, but now I think with trap music and the internet, everything has become more accessible. People are more open now, they accept more stuff, they understand that rappers talk about reality. No matter how rappers speak, people know it reflects what happens for real, they are not fooling themselves. Young people want that, and there is a high percentage of young people in Morocco.

NAAR: Talking about youth, from the experiences you had, do you think society is now quite capable of accepting the youth’s aspirations or are there still things that young people cannot do, or at least not publicly?

S: Umm, well, it’s more in relation to religion, it’s cultural, that’s all. But even that is breaking more and more, it is changing, we can feel it. As I said, people are becoming more open now. Even musically, Morocco is opening its mind to the international stage. So now, Moroccan people accept more stuff. It’s when you’re confirmed elsewhere that Moroccan people will agree to what you do. It’s a bit weird but that’s the way it goes.

NAAR: There are two main generations of rappers in Morocco. The generation of Don Bigg, the first one, that was highly mediatized, committed, supported by power. And the second generation, the trap generation. Shayfeen is a bit between these two generations..

S: Yes, we are in between. My brother Madd, for example, 7liwa, Toto and all, they are from the second generation. The first generation lasted for about 10 years. And the 10 years after are the years of the second generation. We came right in the middle. We released our latest album in 2016, but we only felt its impact in 2017, with all the second generation who started doing the same thing. We were a bit misunderstood in Morocco when we brought trap music in 2012-2013. But we pushed it anyway. We were doing different rap styles because we didn’t want to put ourselves into categories. With time passing and the experience of concerts, we felt that young people wanted that new thing. They want to let their rage out and there is more rage to express through trap than through classic oldschool tracks.

NAAR: There was a field to take over?

S: Yes, well, it’s easier for young people to express themselves on trap songs. I can feel it, it was a game-changer.

NAAR: The trap generation is very popular, but without the support of traditional media and without the support of power.

S: There is a lot of poverty in Morocco, not everybody could afford a phone at the time. There was an elite that had access to the internet at home, they were the ones who could follow rap music a bit. Now everybody is connected, everybody can buy a 2-quid smartphone and check Youtube, follow guys on Instagram and see what they do. This is why now more people are following the movement, they follow they favorite rappers and stuff. It is more accessible even if the media coverage is not great. Lately the media has become more interested in trap, because it is growing fast. They didn’t dare to in the beginning, there was the same roster that was on all radios, the oldschool roster.

NAAR: Beyond the access to traditional media, what do you think distinguishes the two generations of rappers?

S: The former rappers always had the “we don’t have anything in this country” speech, you know. It’s different now. Shayfeen came in a time when everybody was anti-system, everybody wanted to be committed. Either it was to build a career for themselves, because their audience is a population that is not well, that doesn’t live well, so it’s easy to touch people’s hearts. Or they were really committed rappers. You can feel this new wave of rappers don’t need anyone, they say it out loud, they do their thing. I think there is more hope for young people in this new trap generation than with the former generation. With all due respect to the former generation, there is more hope now, it’s purely objective.

[Young people] want to let their rage out and there is more rage to express through trap.

NAAR: But some social problems haven’t disappeared. I have the impression that trap music doesn’t tackle the subject, it is more centred on the individual.

S: Well, that is the illusion, but if you analyze the lyrics, rappers talk about their struggle, their struggle for being able to live here and do what they want. The lyrics reflect all the politics, the state of culture, the state of society. They don’t need to tell things as they are anymore, like “we get nothing in this country, the State doesn’t help us”. That is not what they want to tell anymore. When I started, the vision I had was to inspire as many people as I could to overcome the hardships we experience here, to give people hope. Hope changes everything, even in a pile of crap, if you have a little hope, it changes everything. Shayfeen started from scratch, we had nothing, really nothing, no subsidy, no help, we never signed a deal. But we did the big festivals here and we felt that people didn’t want a music that reminded them of their misfortune anymore. They want a music that shows them everybody can change things for the better. That is the ideology we wanted to convey. It is also a rebellion from us not to make tracks only for the radio. When you are confirmed, even if your speech is a bit shocking or crude, if the public wants you, you can score concerts. There are some lines not to cross though because you are in a kingdom. If you want to really go against the flow and act like crazy, it’s like shooting yourself in the foot. You will give a stop to your career, while you should be changing things and give hope.

NAAR: I have the impression that Shayfeen’s tracks have evolved towards trap more and more. Has it been difficult to make your music evolve?

S: No, because we have been making trap before it was trending in Morocco. We started in 2012-2013. On our first mixtape in 2012, there are 2 purely trap tracks that I produced myself. In the beginning, we didn’t dare making too much trap because people didn’t understand it. People knew one rap style, they didn’t have a hip-hop culture. The old roster had imposed a certain style, that was highly mediatized. It matched a certain image of Moroccan rap. But rap isn’t really Moroccan, it can be in Darija but it is universal. It is American but it has become universal. You cannot say there is a Moroccan rap, with a type of lyrics, of instruments. The second generation couldn’t stand that anymore. Your question was about our musical evolution towards trap. We started with doing many different styles, not just trap, to see what could work, what we liked. That is why we wanted to experiment when we started going on stage when we were young. When we were doing low tempo songs that talked about problems, people didn’t react. But as soon as we played trap tracks, on which you can lose control and say fuck everything, you don’t say fuck a particular thing, you say fuck everything, people reacted immediately. They want to say fuck everything too. I think trap music is a new way of rebelling in Morocco.

NAAR: All the musical research you are talking about conveys the idea that Shayfeen is not just a trend but a band of real musicians that is here to stay. What are the other aspects and ambitions of your project?

S: Our ambition since the beginning has purely been to give hope, to export this music and to show elsewhere that here in Morocco, or in other countries in which people think there is nothing, we can do good stuff and give hope to the world. We always ambitioned to get a fucking good musical level because our inspiration came from the US at first, I didn’t listen to much French rap. We wanted to match the level of US rappers, even with limited means. That is why we evolved musically. It impacted me a lot as a composer. This and the fact that I listened to a lot of different musical styles as a child, with my father for example. It broadened my musical brain and it reflected on the group’s music and Shayfeen’s music. We wanted to try and build a fucking industry, that was the idea. We know that music can take you to a lot of places. For example, I produce tracks, in France too, for Lacrim. Our dream was to meet other people, to grow musically and why not build an industry. I think it is more interesting for young people to have an industry here than to scream that there are problems. We wanted them to have jobs. Three or four years ago, we decided to create a collective [WDS – Wadrari Squad] and I tried to gather a lot of composers and a lot of rappers to try and give structure to ourselves, before even having the right structures. We had quite an impact here in Morocco and a lot of young people contacted us. So we created this collective, we collaborate with one another, I can produce tracks for the guys, try to build a network for us. We collaborated with artists outside of Morocco, even before the collective, to try different musical styles and build a little market here in Morocco. Maybe we will make other industries want to come here. Big rappers come here now to be produced, to get toplines or beats from here. We have everything here but the industry. This is why we collaborated on NAAR’s project, that we worked with Lacrim, that we try to make as many tracks as we can, for everybody, not just the Moroccan market. I think language is not a barrier anymore with the trap movement. It is more about musicality, melodies, that is what matters, that is the new language.

NAAR: Well, yes, when you look at Young Thug for example, there are a lot of songs in which the lyrics are not the most important thing, it is more about the emotion he puts in.

S: That’s it, the vibe talks for itself. We wanted to do just that, a music that people will listen to even if they don’t understand the lyrics. We tried to reach the level of US productions, in terms of visuals and flows too, we tried to get the whole pack. We understood that by analyzing the American industry, the good rappers, what they do, how they follow the trend, to get something concrete. And it worked, I think it worked, because sometimes 5 out of the 10 Youtube trends in Morocco are Moroccan rap music videos. There is a lot of rap in Morocco now and it deserves to be seen by people elsewhere.

NAAR: How many people are there in the collective?

S: We are maybe 10 people in our collective, between composers and rappers/singers. There is Madd for example, XCEP who raps both in English and Darija, there is West, Yo Asel who is a composer. By the way, Yo Asel sent French Montana’s manager some demos, and French took them for a track. Since Yo Asel suited French Montana, people discovered his work and now they want to work with him, he produces upcoming rappers in the US. The whole team produces quite a lot of people, we are comfortable with everything, with the flows, the toplines, the beats. We rap, yes, but for the collective we have the ambition to bring our Moroccan touch elsewhere and see how far our impact can go.

NAAR: Speaking of opportunities, do you consider you have the same opportunities as European artists?

S: Here in Morocco? No, no! We don’t have copyright. There is no industry. People don’t buy music, even if they have phones, not everybody can have a bank account and buy tracks on the internet, so streaming isn’t great. There is no network to organize concerts, no venue to make your own tours. But musically speaking, we have everything, even to match the American market.

NAAR : I also meant on an international level?

S: Well, we can produce people elsewhere. Right now, I’m working with my team on a project for Sony. I produce and do the art direction, the artist is a Moroccan girl that we signed here [Manal]. I wanted to show that we can have quality products here. It would be good to have a proper industry though, even for the economic well-being of the country. Now we are working with Sony Middle East, it is the first time they have signed a Moroccan artist, who raps a little and who sings pop music in Darija, and not just oriental music. We produced 2 or 3 tracks for her and they ended up wanting to work with us on the whole album. We are paid with fees because you cannot have full copyright here in Morocco. There is the BMDA [Bureau Marocain des Droits d’Auteur – Moroccan Office for Copyright] but it never sends you your money. It’s tough here, but you just need to have the right vision, the intuition to lead your career the right way and try and change the situation for the best. We want to use our impact to be able to have an industry here one day and to be the ones who helped it take shape, you know.

NAAR: What about Europe’s visa policy? Moroccan artists are rather restricted in their mobility, do you think it has slowed down your development? Does it still? Do you have examples?

S: Yes, a lot of people are denied their visas. We had visas denied for a concert in the United States a long time ago. It’s a bit tough but we went to France, to Norway and we were not denied the visas, even if we didn’t have our artist cards. Now it seems that the artist card has become mandatory, but it is not very useful here. We just forgot to do it but in the beginning, nobody wanted to do it because it was a way of saying no. Why would you make your artist card if you don’t get anything in return? We did a lot of radio, a lot of festivals, but you don’t receive anything on your own productions. We can even create revenue for this country, when we do concerts or produce people somewhere else. And yet if you don’t have the artist card, they can prevent you from doing a concert, even if you have a big audience. In Morocco it’s about control, they want to control everything, to look at everything, to know what will be released, what won’t be released. There are now artist subsidies you need to have three albums to get, but if you already have 3 albums, why would you apply for a subsidy? They tell you you need three albums so that only artists who are already in the Ministry of Culture’s roster can get it. It is a form of control.

NAAR: What interested you in NAAR’s project?

S: It sticks to our vision, mine and our band’s. Since 2012, we always collaborated with artists, in Canada, in France. I listen to a lot of rap on Soundcloud, producers, upcoming rappers, I was listening to Gracy Hopkins, Easy Dew, people Mohamed [Sqalli] told me about. I like experimenting music, art is free. I couldn’t experiment as much as I wanted to in Morocco in the beginning. When you collaborate, when people see that other artists do stuff abroad, they accept to see a Moroccan do the same thing, it’s a bit weird but that’s the way it goes (laughs). Also we want to collaborate because we want to meet other artists, learn from people, see the industry abroad.

NAAR: Can you tell me how your collaboration on the project went?

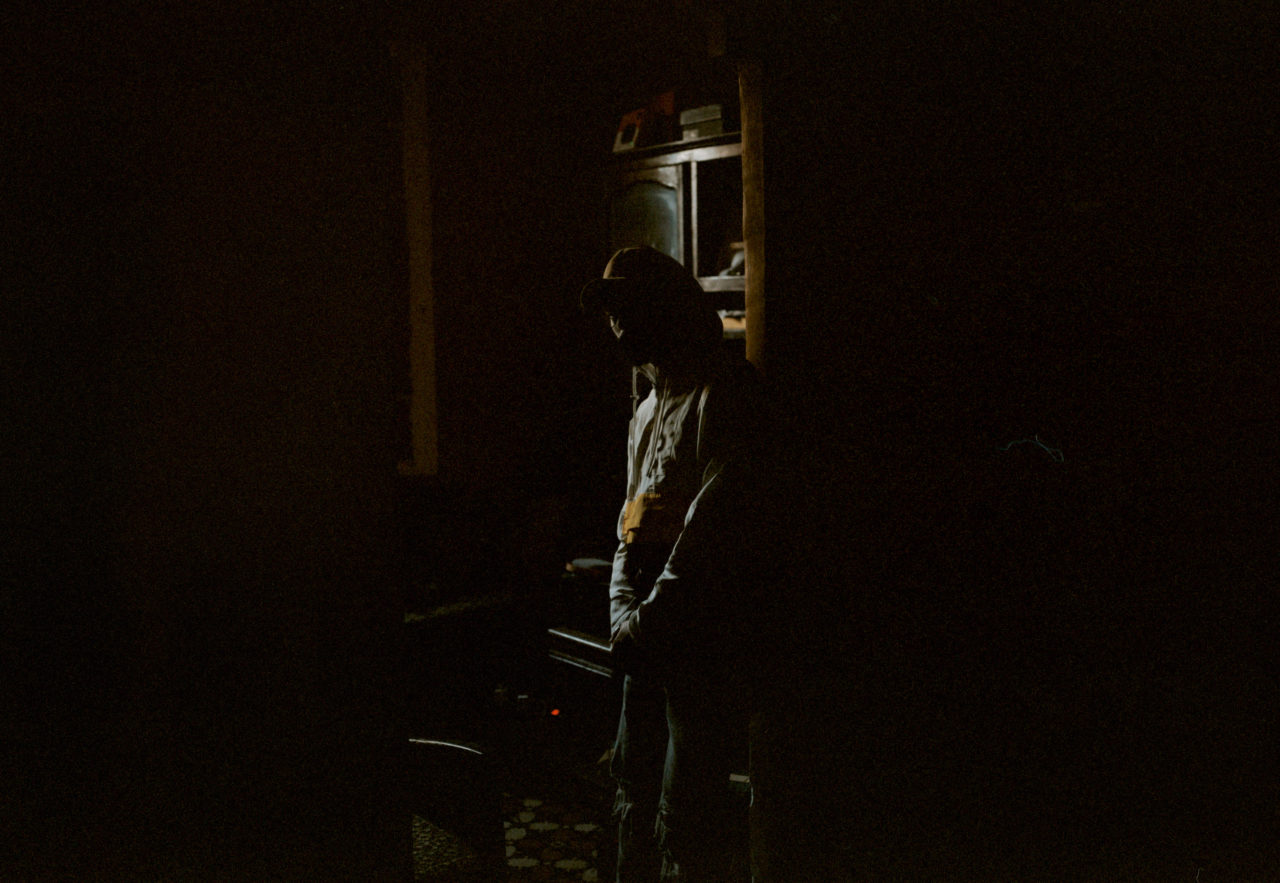

S: It went really well. We came [to the residence] on the first day, just to see the guys. I wanted to record with another dude in the beginning, who was not there eventually. Laylow was supposed to record with another rapper. We came back on another day and Mohamed asked us if we wanted to record with Laylow. I like Laylow too, I like his tracks, his music videos. Easy Dew was there also, we listened to the beats and chose one. It all happened smoothly, it was great. When the vibe is good, things are done quickly. The track speaks for itself, there is a feeling, even the music video matches the vibe we wanted to get across. We don’t convey messages there, we get vibes across. This is why I like collaborations, you can always experiment other people’s universes, other people’s beats, try to blend your vibe with the vibe of other rappers and mix the whole thing between three or four brains. This is why I founded my collective. In the beginning, I was producing all my tracks but at some point I realized that it is even better when several brains work together. I knew it was going to go really, really well with Laylow. Collabs are more of a feeling, a feeling that has to be built beforehand. It is why we came a day early, not to record, but to meet the guys, talk, share ideas, and then to collaborate. It was a really great vibe, even during the shooting of the music video. I didn’t expect that because the track with Laylow wasn’t planned. That is what’s beautiful musically when you make collabs.